Unfunded and Underfunded Priorities

From a Local Government Perspective

- When it comes to State obligations or priorities, there is a clear connection to the role of the State’s political subdivisions, even as there is an interdependence.

- The State’s obligations translates into resourcing and implementation – if it can’t do one or the other, or both, it relies on local governments to fill the gap.

- At the same time, the State’s obligations or priorities reflect some of the fundamental building blocks of communities. State services to Alaskans translate into more sustainable communities, healthy and educated residents, jobs, and lower cost and higher quality of living.

- State services that are delivered at the local level depend on adequate State resourcing, even as they are expressions of local control.

History of Underfunding

- State spending has not kept up with inflation and the growth of Alaska’s population.

- That’s important because it means that out of a diminishing budget, over time, the State’s doing less with less, and/or shifting the costs and responsibilities to others.

- Choices of spending come at the expense of other choices, with little flexibility and a dwindling number of options.

- That race to the bottom increases conflict over limited resources.

- Some of Alaska’s spending can be attributed to a boom-and-bust cycle.

- When revenues are booming, the State has felt more comfortable increasing statewide expenditures and allowed the slow growth of operations; mainly it has used booms to fund capital projects and place as much as it can in savings.

- When revenues have bust, the State has eliminated capital budgets, eliminated statewide expenditures, and slowed growth.

- Every boom feels like a chance to make a difference; every bust a chance to work on a fiscal plan.

INFLATION

State spending not keeping up with inflation

- This chart from Legislative Finance (an independent, non-partisan arm of the Legislature focused on fiscal research and analysis) is probably the most useful way to look at how State spending has declined over time, if you adjust for population growth and inflation.

- It’s easy here to see the booms – the yellow and bright blue clearly show that funding becomes available to address infrastructure needs and statewide operating.

- Statewide operating includes things like funding for local governments, school construction, and debt obligations. It can be thought of in terms of costs that would normally be there but that can be shifted to another party if the State needs to. The reality is that the other parties have little capacity to pick up those costs.

Community Assistance

- A good example of a statewide operating cost is the intergovernmental transfer of State resource revenue to political subdivisions of the State, which are performing services that would

otherwise be provided by the State. - Initially revenue sharing tied to police, fire, roads, etc, the program has evolved over time, with negotiated – sometimes – reductions when the State couldn’t afford to maintain its previous level of funding. Local governments came to the table and compromised at lower levels so that other priorities could be maintained.

- Of course, these State expenditures aren’t tied to inflation at all, so when the program is adjusted for inflation, it is easy to say that the value of today’s distribution, instead of $30 million, should be $300 million. That’s the difference inflation and reductions have made over time, which local governments make up the difference for.

Community and Regional Jails

- Community and Regional Jails is how this program is characterized by the State. These are municipal-owned and operated assets that are in place to provide a service to the State. Essentially, the role for local jails and corrections officials is to provide a space to hold prisoners until such time as the State can prosecute a sentence.

- Since Alaska has a unified court system, which the State is entirely responsible for, if these weren’t in place it would fall to the State to do this on its own. The combination of Troopers and Dept. of Corrections time would go well beyond the costs of local delivery of this service.

- Since the bust in 2015, the State made up a new number – $7 million, and has kept it there for 6 years. Contracts haven’t been renegotiated, and local governments pick up the difference. That means that local governments are covering as much as 50% of the cost of operating a jail that is 90% in place for State operations.

Senior Exemption

- State law exempts real property owned and occupied by residents 65 or older, or a disabled veteran, or widow aged 60 of either.

- The exemption applies to the first $150,000 of assessed value. It’s an exemption that is broad in its applicability, though best practice would change this to needs-based.

- The State has not funded the reimbursement since 1997, though it is required by Statute to do so.

- The effect of the unreimbursed exemption is that the property tax must be higher to make up the difference, and/or it falls to other taxpayers to make up the difference.

Alaska Marine Highway System

- A lot could be said about the Alaska Marine Highway System, and its gradual erosion within the State’s budget.

- To think that this investment was one of the first by the new State after it became one, with a vote of the people on a bond that funded its establishment, conveys in part just how important this is to many Alaskans.

- The return on the investment is clear – about $2 to the economy for every $1 in State support. But since the State’s budget isn’t tied to the economy through a broad-based tax, it doesn’t feel that return. So it just looks like a cost it can’t afford during down times.

EDUCATION

Base Student Allocation – School Funding

- This is probably one of the clearest examples of how inflation affects a State obligation – public education is a requirement of the Constitutio. There’s no equivocating about the role the State must play in maintaining a system of public education. In other states, courts have found that this means very directly that the State is responsible for funding that system at an adequate level.

- The way the State’s formula works is that it establishes a “Base Student Allocation” that incorporates a lot of different factors but can be thought of as its assessment of what is adequate to fulfill that obligation.

- The State has kept the BSA flat since its 2015 bust, at $5,930. That’s $200 more than it was the four years prior.

- This plays out in districts as the same amount of funds each year per student for costs that have increased by at least 1.5% each year. Energy, healthcare, and pensions have all jumped by much more over that time. Districts then become less able to utilize these funds for instruction while they’re plugging holes in administration and maintenance.

Base Student Allocation – Adjustment Inflation – FY19 Dollars

Planning for Growth

Is there a right way to think about how these programs, or State spending generally, should be limited or grow?

- It’s important to plan for growth, even if you believe it should be limited. Limiting growth has value because it means that revenues that come from individuals and the private sector are also limited. But budgeting for some level of growth also has value because individuals and the private sector depend on government services and capital outlay.

- There are numerous ways to plan for managed growth – managed growth means that the State is being intentional about its spending, limiting growth to the level that contributes to economic growth and meets its priorities and obligations.

- Every year the Governor is required to produce a 10-year plan, released by its Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OMB includes an inflation adjustment in State operations that inflation should be tied to. That rate is 1.5%, but again only applied to some things, and generally not to intergovernmental transfers, statewide programs, or even capital projects. The Permanent Fund Corporation plans for 2% inflation, and our pension system assumes 2.25%.

- Alaska’s GDP growth since 2000 has only been 1.11%, which is reflective of the boom and bust cycle, too. If oil is removed from GDP the picture is of steady growth over that time.

- Permanent Fund Growth averaged over the last 10 years is at 8.4%. The difference between the return on our savings relative to economic growth that hasn’t kept up with inflation is critical. The State has to think about how to leverage the one in support of the other, or at least that is one option ahead.

- More recently, the US Treasury used 4.1% as the average national growth rate of revenues, as a way to measure whether the State and local governments have seen lost revenue during the pandemic.

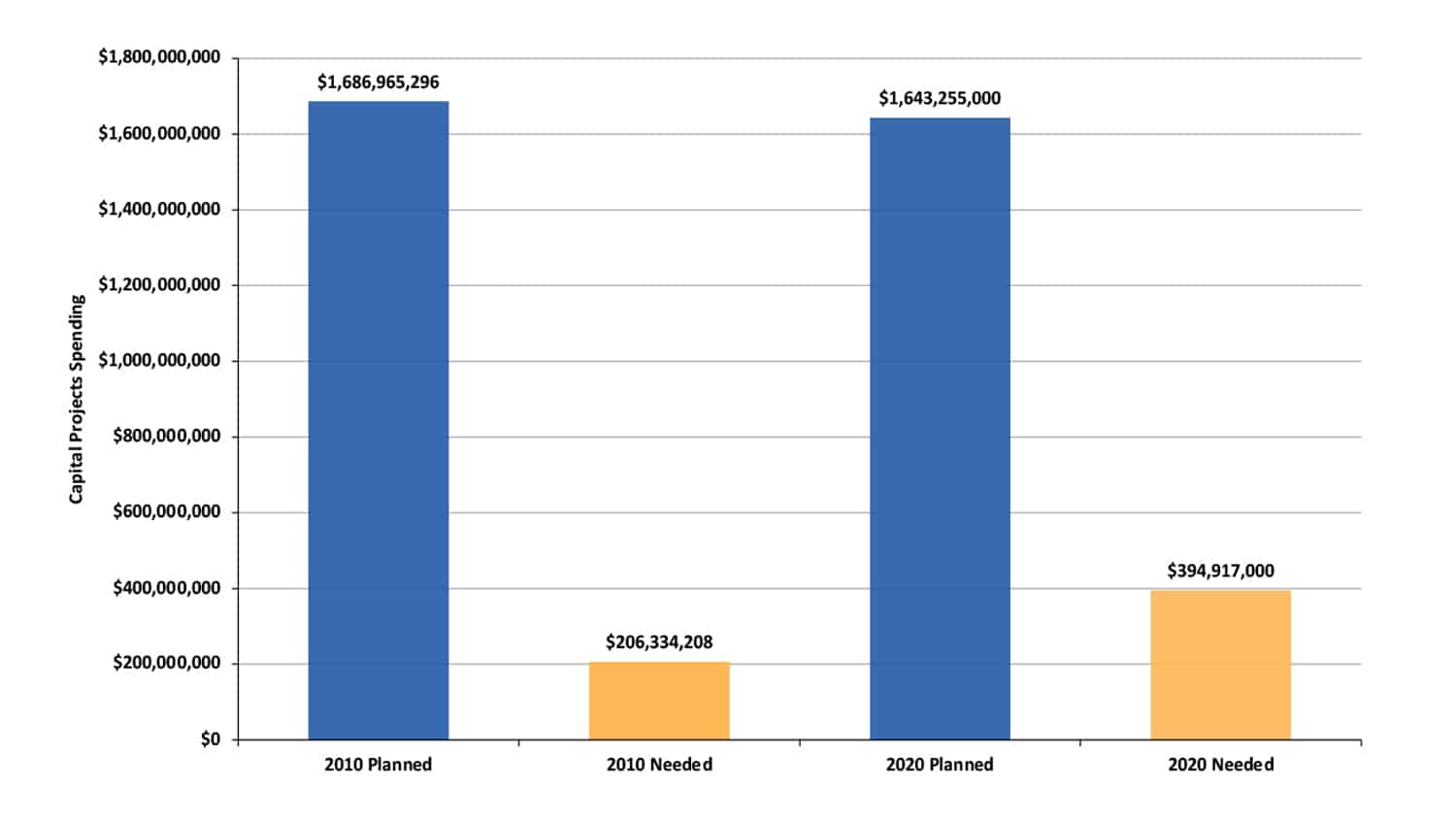

How do we plan for billions of dollars in infrastructure needs, in terms of time and resourcing?

Here is a snapshot of some of the estimated needs for capital construction and maintenance, the total followed by what the State’s budget includes for:

- School construction and major maintenance = $2.3 billion ($17 million or .07%)

- Water and Wastewater – rural = $1.6 billion ($86 million or 5%)

- Water and Wastewater – urban = $1.6 billion ($0)

- Local capital needs = $4 billion ($10 million or .02%)

- Port and Harbor needs = $389 million ($14 million or 3.5%)

- State deferred maintenance = $2.7 billion ($50 million or 1.8%)

- STIP = $5 billion ($1 billion or 20%)

- Broadband = $2 billion ($10 million or 0.5%)

- Jails = $500 million ($0)

- Housing = $9 billion

WATER AND SEWER

- Water, sewer, and wastewater systems are foundational elements of a community. Businesses and residents depend on these as much as they do power and transportation.

- The way the State approaches water and sewer investments is to leverage federal funds. The federal Indian Health Service maintains a list of needed projects, with about $1.9 billion in needs listed for eligible communities. Some funds flow directly to ANTHC, and the State’s match of about $80 million each year flows through DEC.

- For communities that aren’t eligible, they either utilize the State’s revolving loan fund, or take on debt or increased costs on their own.

- The majority of water and sewer systems are owned and maintained by incorporated cities, many of whom struggle to afford necessary upgrades. Many water and sewer systems are in dire need of improvements.

Water and Sewer – Who pays?

- The majority of funding for water and sewer improvements is from the federal government, though this fails to capture local contributions.

- Local governments with the tax base to support it have utilized the State’s revolving loan fund – established through federal funding – to address nearly 300 projects, borrowing a total of $538 million.

- Others improve their systems through higher fees or rate increases, or through voter-approved bonds.

SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE

- Alaska has roughly 1,000 schools – nearly half are 40 years or older, the average replacement age for facilities. Of the total, 757 municipal owned/maintained schools.

- Construction and major maintenance are critical components of the State’s Constitutional obligation to establish and maintain a system of public education. The way the State approaches this has been through two programs – school bond debt reimbursement and a grant program.

- Both require a 30-40% match from municipalities with school districts, and a minimal amount from other districts, called REAAs (Regional Education Attainment Areas), which are the responsibility of the State.

- Of the grant programs, the State requires school districts to submit priority lists of needs each year, which then it has funded on average 8% of. In recent years, the State has shifted its reimbursement of school bond debt back to local governments. There remains roughly $1.6 billion in need according to priority lists, and about $800 million left in school bond debt.

- Industry standards indicate that 2% of building value is needed, annually, to meet capital renewal needs of existing buildings… and suggest an additional 1% of replacement value… for deferred maintenance. At $9.4 billion, the annual amount for Alaska would be $283 million. The average annual funding over 11 years is $69.5 million, state and local share, through the grant program. Through debt reimbursement, another $65.7 million annually in project value is added for a total annual amount of $135.2 million – helpful, but only 48% of the forecasted need. DEED, 2021

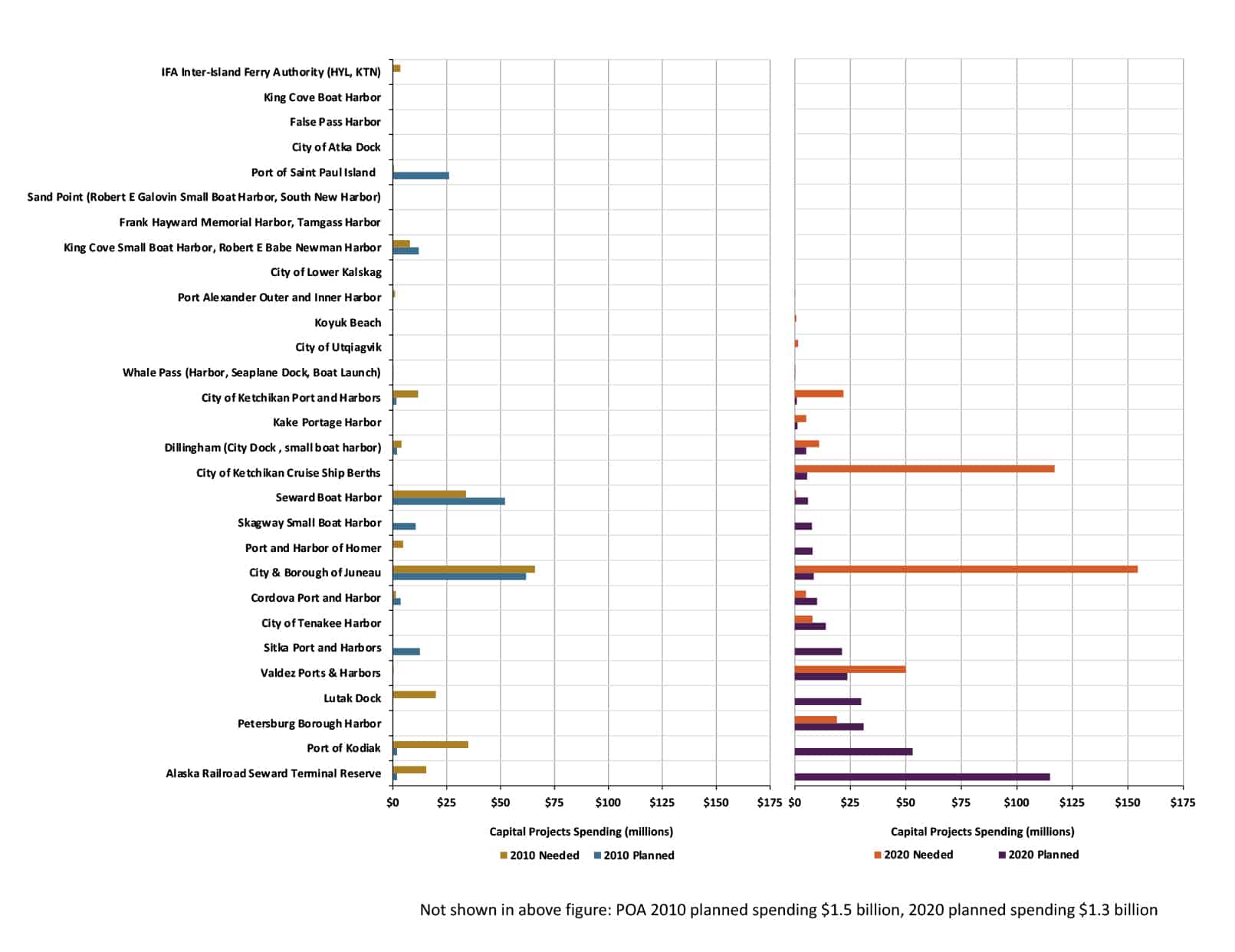

PORTS AND HARBORS

- Alaska has more coastline than the rest of the nation combined. Coastal communities have active economies dependent on port and harbor infrastructure, which support both the fishing and tourism industry, as well as provide freight. The vast majority of Alaska’s freight comes through its port system, which means all Alaskans rely on functional ports.

- These ports and harbors are municipal assets. The State transferred most of its coastal infrastructure to municipalities in the 1980s. Of 133 public ports and harbors, local governments own and maintain 117, 82 of which were transferred by DOT.

- These ports were in need of repair when transferred, and the State set up two ways to make up for this. One, was a commitment to reimburse the debt that some local governments took on to make those repairs. This reimbursement was unfunded in the most recent budget.

- The other program the State established was the municipal port and harbor matching grant program. Local governments match State funding with 50% of the project’s costs. Of 98 grants requested, 45 have been awarded. Basically, the State has not funded the program half the time.

- There are no port and harbor improvements in the State’s planning documents, except for ferry terminals. The total estimated need in 2020 is at least $389 million, and likely much more.

CHILD CARE

- Child care in Alaska is not a public service, except as limited pre-k; otherwise, it is delivered by private providers. However, the State provides child care assistance to families in need, through the Dept. of Health and Social Services, utilizing federal funds. About $8 million in State funds serves as a match for $30 million in federal funding.

- thread Alaska has done a great deal of research on need across regions of the state.

- Out of 60,000 children under age six, 13,000 don’t have the care they need

- The average cost of child care per household is 17% of annual income

- 25,000 children are at home, with a parent not in the workforce

- Available child care and cost vary greatly by region of the state. Cost can be as much as 27%, and the gap in care as much as 70%.

- The bottom line is that child care is critical infrastructure support for parents participating in the work force, businesses employing parents, and serves as an economic driver for the state. Access to high-quality early childhood education is going to help Alaska’s families confidently return to the workplace knowing their children are safe in high-quality programs.

- Alaska’s early childhood education system is an essential part of the economy, enabling families to work while employing a significant workforce. Before the pandemic there was 496 childcare providers. By April, half of the childcare providers had closed and by May 205 childcare providers were still closed. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of childcare for families to be able to fully engage in the workforce and provide financial stability. 87% of people with children in childcare rely on it to work. In that sense, childcare is essential to the economy of Alaska and can be viewed as critical infrastructure to support the economic system.

- Alaska has unique challenges in providing affordable, high-quality childcare to all children who need it. Prior to the pandemic, the demand for high-quality childcare surpassed the available supply. COVID-19 has compounded the situation and had a devastating negative impact. In a recent thread survey, more than 50% of programs are concerned about having to close this year with 63% of programs reporting that they needed additional funding.

- Access to quality, licensed and regulated, child care is difficult and unaffordable. High quality care is even more difficult and is not well defined or available to support families. Families want and need more choices for their children’s care in order for them to access the work, training or career they desire.

- Another stat to note is that Alaska is one of just 4 states that have not increased investments in early childhood funding/supports in the last 6 years. A good national resource to reference can be found here.

- In 2019, Alaska’s early childhood education sector accounted for more than half a billion dollars of economic activity annually from families being able to work. It creates an estimated 8,700 jobs with $375 million in labor income and another $587 million in economic activity. Alaska’s economy would be negatively impacted without this activity (or a reduced level of this activity). Every dollar spent on early care and learning generates $1.50 in economic activity. Child care workers on average make $13.21 an hour.

- Statewide there are some 60,188 children under the age of 6. Of those 13,204 are in need of some form of early education or day care program, or a gap of 22%, representing the gap between need and capacity. The average yearly cost of licenses daycare statewide is $13,775.00. See more detail and graphs here. In recent surveys, 56% of respondents found it difficult or very difficult to find early care and learning services which is up from 46% in 2015 for children under 6. It is also harder to find child care in rural than urban areas. One in five households or 22% can’t participate in the workforce because of a lack of or the cost of early care services. View the thread study here.

- Cost of daycare is also a major impediment. Cost of licensed daycare as a percent of median income is as follows:

- Married Couple Household 12%

- Single male household 23%

- Single female household 34%

- Most Important Factors in Difficulty Accessing Child Care or Preschool Programs are Quality (Q), Availability (A) and Cost (C)

- Statewide: 20%(Q), 28%(A), 51%(C)

- Urban: 22%(Q), 22%(A), 56%(C)

- Rural: 14%(Q), 50%(A), 36%(C)

BROADBAND

- Broadband in Alaska is not traditionally delivered by the public sector, though most of the investment has been through federal grant, infrastructure, and formula programs.

- Broadband is critical for efficient government, economic development, and Alaskans improved quality of life. Unfortunately, the majority of Alaska’s communities rely on less than 10Mb speeds. Internet speeds are easily described as deficient in much of rural Alaska, especially.

- The State has convened a number of task forces to work through this issue, has identified goals related to improvements needed, but doesn’t have a role in regulating the industry. One of the more important roles of the State is mobilizing and coordinating federal funding to meet the needs it has identified, and closing the gaps.

- Local governments have had less a role even than the State, in many ways. One local government – the City of Ketchikan – is the only municipal-owned telecom provider, with some of the fastest speeds and redundancy in the state. There do exist many community-owned cooperatives, however.

The State’s 2019 Broadband Task Force found

- Some 21,000 households in Alaska currently are not served by broadband, and more than half the nation’s anchor institutions (hospitals, schools, libraries, municipal or borough governments, etc.) with insufficient broadband capabilities are in Alaska. So, what would the opportunity to access greater Internet speeds produce? Economic impact projections based on most recent demographic and employment numbers from the 2011 Census show that a 1 percentage increase in broadband adoption could result in growing the Alaska economy by $67.7 million.

- Other benefits would include:

- 1,890 jobs saved or created

- $49,184,413 in direct annual income growth

- $221,743 in average annual health care costs saved

- $2,536,553 in average annual mileage costs saved

- 1,256,220 in average annual hours saved

- $15,715,316 in annual value of hours saved

- 3,276,906 in average annual pounds of CO2 emissions cut

- $19,933 in average annual value saved by carbon offsets

HOUSING AND HOMELESSNESS

- Efforts to address affordable and/or sufficient housing, and homelessness, are increasingly relevant to improve the cost of living in Alaska, as well as public welfare.

- Multiple nonprofit agencies work with and through federal, state, and local agencies to improve conditions.

- While homelessness may be more prevalent in urban communities, what is less visible is overcrowding, which is often the case in rural or remote communities. Housing, though, is a statewide challenge, both in terms of its affordability and accessibility.

- HUD estimates the total costs to solve overcrowding to be $7 billion in Alaska.

Housing and Homelessness by the Numbers

- 1949 homeless on any given night in Alaska in 2020

- Of those 224 are unsheltered and 1,725 are sheltered

- 26.6 people per 10,000 are homeless

- 2.2% change from 2019

- 18.7% change from 2007

- Up 22% over last decade

- 1,445 are individuals

- 504 are people in families with children

- 188 are unaccompanied homeless youth

- 327 are chronically homeless individuals

- 94 are veterans (Source)

- Public school data reported to the U.S. Department of Education during the 2017-2018 school year shows that an estimated 3,769 public school students experienced homelessness over the course of the year. Of that total, 351 students were unsheltered, 678 were in shelters, 222 were in hotels/motels, and 2,518 were doubled up (Source). Almost half of the homelessness population is in Anchorage. Alaska Natives make up a disproportionately high percentage of Anchorage’s homeless community — about 45%, although they make up about 15% of the state’s overall population. PsyDPrograms.org released a study on the State of Homelessness in America using data through 2019 from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The study includes state rankings on the overall homeless population, as well as numbers on women and children. Here are key findings in Alaska:

- No. 8 highest homelessness rate, 260.7 per 100,000 people.

- No. 22 highest percentage of women in homeless population, 39.9%.

- No. 30 highest percentage of children in homeless population, 17.6%

- Alaska has one of the highest rates of homelessness among women according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Some 37% of Alaska’s homeless population are women while the national average is 29%, statistics from the coalition found.

- Homeless is a medical condition under the International Classification of Diseases, the diagnostic manual that doctors use, it’s a billable code. The average age of a homeless person to die in the United States is 50, about 28 years younger than the normal life expectancy. While homeless individuals die from the same causes as the general population, they experience these illnesses at rates three to six times higher, according to the National Health Care for the Homeless Council.

- Anchorage:

- Anchorage spends tens of millions of dollars every year addressing homelessness. An estimated 1,100 people are officially homeless in Anchorage, and some 7,900 sought some form of homeless assistance in 2019. Around 80% to 90% of the women who seek homeless services in Anchorage report being survivors of sexual assault. In its July report, the Anchorage Coalition to End Homelessness found that Alaska Native residents constitute nearly half of the city’s homeless population and more than 75% of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Census data indicates Alaska Natives make up just over 9% of Anchorage’s population. The report released Monday by the Anchorage Coalition to End Homelessness analyzed supply and demand, including the housing and support services necessary to get people off the streets, out of shelters and into suitable living arrangements. In 2019, about 7,900 people in Anchorage sought some form of assistance because of homelessness, up from 7,763 from the prior year. During a single night in January 2020, Anchorage’s official homeless population was 1,058, with 1,003 people in shelters and 55 living outside. Anchorage needs 1,695 more rapid rehousing units and 700 units for permanent supportive housing, the report concluded. An estimated 373 are chronically homeless, costing society an estimated $47,000 each annually in criminal justice, emergency response and medical treatment, according to a May 2018 study commissioned by the United Way of Anchorage.

- According to the Anchorage School District’s Child in Transition program, 1,686 enrolled students were considered homeless this past winter, many of them living in motels, doubled up with other families, couch surfing or staying at Covenant House. Including young children and those who are homeless and eligible to be enrolled in school but are not, the count increases to 2,420.

- At least $32 million is spent annually by various entities trying to deal with homelessness in Anchorage, according to research by the Anchorage Homeless Leadership Council

CONSTITUTIONAL OBLIGATIONS

Public Education

Public Health

Public Welfare

Permanent Fund

Public Safety

Alaska’s Constitution provides a straightforward list of the State’s responsibilities in Article 7:

- Public Education – The legislature shall by general law establish and maintain a system of public schools open to all children of the State, and may provide for other public educational institutions. Schools and institutions so established shall be free from sectarian control. No money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.

- State University – The University of Alaska is hereby established as the state university and constituted a body corporate. It shall have title to all real and personal property now or hereafter set aside for or conveyed to it. Its property shall be administered and disposed of according to law.

- Public Health – The legislature shall provide for the promotion and protection of public health.

- Public Welfare – The legislature shall provide for public welfare.

While these are presented simply, the result is ambiguity about what exactly each responsibility means. What consists of public welfare? How is a maintenance of a system of public schools to be paid for and implemented? How extensive is the responsibility for promoting and protecting public health? Can these obligations be delegated or shared? Who pays? These questions are at the heart of political debates.

Beyond this list, the State is responsible for natural resource management, a unified court system, and public safety. What about transportation and infrastructure?

PUBLIC EDUCATION

- Maintaining a system of public schools means the State is responsible not just for providing adequate and equitable funding for student education, but also ensuring that schools do not fall into disrepair.

- Adequate State funding means that school districts have enough funding to meet instructional needs and to ensure educational attainment – enough teachers working to make sure students succeed.

- Equitable funding means that those districts with less access to a local contribution, or who have higher costs, have just as much available for that instruction and student outcomes as those districts with greater access.

- The State has a clear role in helping to pay for the construction of new schools, where the population has grown or to replace old schools, and to ensure that maintenance occurs. Where maintenance does not occur – where a district cannot afford to fix things along the way – it is more likely that costs will be higher in the future as the problems worsen.

- A recent Task Force on Teacher Recruitment and Retention found that education professionals identified “adequate compensation for assigned duties (salary)” as of most personal importance, with retirement and healthcare benefits # 3 and 4 on the survey. The survey looked to at what solutions would most influence retention and recruitment, and found that a “competitive salary commensurate with cost of living” was the #1 need; retirement benefits was #3. The Task Force took up no recommendations related to pay or benefits.

- Interestingly, from NCSL data listed below, Alaska has some of the highest K-12 per pupil expenditures in the nation, coming in at #4. However, if you look just at salaries, Alaska places just ahead of South Dakota (ranked 25th overall and just ahead of national average) as a % of total spending.

- Actually, Alaska is tied for 5th for spending as it relates to all other functions as a % of total spending. It’s just expensive to provide education here, even as salaries are well below that national average and benefits on par.

Public Education – Pre-K

- Alaska ranks 42nd in the nation for access to PreK.

- There are 19 school districts with PreK; in addition, 3 school districts with PreK partner with Head Start; 4 school districts align PreK and SPED; 2 school districts have PreK, SPED, and tribal combined. Total, there are 28 PreK programs that involve school districts; and within the 28, there are 17 that are State PreK grant funded programs.

- Head Start programs receive 80% of their funding from the Federal Head Start Office; these are considered federal direct grants to the grantees and do not pass through DEED. Each Head Start is on a different funding cycle, so programs receive their federal funding at different times. The FY2020 federal allocation was approximately $58 million. Programs are required to provide a 20% non-federal share, which the $6.8 million in state general fund dollars in DEED’s budget can be used towards.

PUBLIC HEALTH

- The State is the primary provider of public health, followed by or at the same level as tribal health. Very few local governments have public health “powers,” which simply means that they haven’t adopted laws or had voters approve laws that would fund the delivery of local public health.

- About eight local governments do own municipal hospitals, almost exclusively in coastal, islander communities who experience high inflows of tourists or the fishing industry.

- Public health and well-being is crucial for the sustainability of Alaska’s communities. Local governments work within this space daily.

- From the Kids Count data: Alaska ranks 47th nationwide for economic well-being. 23,000 Alaska children (13%) live in poverty, 75% of Alaskan 4th graders are not proficient in reading and 71% of 8th graders are no proficient in math (this might be good in the education section), 44% ranking nationwide for health.

Health Funding

In Public Health there is a large increase in funding for the emergency programs in FY 20 and 21. The program increases from $10.84 mil. in FY 19 to approx. $115.06 and $115.46 million in FY 20 and 21 respectively.

(Note the behavioral health numbers exclude any funding for API. API funding has increased from about $30-$33 million from FY 11 to FY 17, to $36 million in FY 18 to $43 to $55.6 million from FY 19 to FY 21, in part due to federal and state compliance issues.)

- In an assessment of how well Alaska has done over the past year to improve the statewide health of all Alaskans, Healthy Alaskans has released data showing that Alaska has met the target for or improved on 12 of its 25 health goals. Here are a few highlights of the progress made, as indicated by the HA2020 all Alaskan Scorecard. Overall, Alaska has:

- Reduced the cancer mortality rate.

- Increased the percentage of adolescents (high school students in grades 9-12) who have not used tobacco products in the last 30 days.

- Reduced the rate of unique substantiated child maltreatment (age 0-17 years).

- However, the data shows that there was a downward trend on many of the health goals. On 19leading health indicators Alaskan’s health was not improving or had declined. Two out of three Alaskans have an underlying chronic health concern.

- The State of Alaska currently has some of the highest per capita rates of substance abuse and tobacco use in the nation. Reduction in traditional labor force earnings due to drug-impaired productivity were the second largest productivity-loss category. In 2018 it totaled $161 million.

- In 2018, the estimated costs of drug misuse borne by state and local governments, employers, and residents of Alaska was $1.1 billion. Most of the costs shown in the table below—those associated with criminal justice and protective services and public assistance and social services—are borne by the public sector. A significant portion of the health care costs are also a public expense, largely because they are covered by Medicaid. The remaining large category, productivity loss, affects individuals, families, and public and private employers across the full range of the Alaska economy. In SFY2019, the Division of Behavioral Health provided approximately $4.3 million in state- funded grants for prevention of drug misuse.

- In SFY2019, the state spent $227 million on social welfare programs, of which approximately $3.1 million (1.4%) was to address drug misuse.

- An estimated 5.9% of total justice system spending (state, federal, and local) in Alaska, $123 million, is attributed to drug misuse arrests and offenses in Alaska. If the same rate is applied to total state Undesignated General Fund spending on the justice system ($620 million), about $37 million of that spending is attributable to drug misuse. This figure is likely conservative, as Alaska likely covers a greater percentage of its justice system costs with state funds than the average of other states.

- More Alaskans have died of unintentional drug overdoses in Alaska in 2020 than during each of the previous two years. On June 7, 2021 the Dept. of Health and Social Services issued a public health alert about the increases in overdoses in Alaska. The average number of overdoses per week since March is almost three times as high as the weekly average in 2019 and 2020. Increases are highest in Anchorage, Mat-Su, Southeast and the Gulf Coast. The use of Narcan for overdoses has increased from 20 uses in February to 60 in March and it has remained high through June. (ADN June 7th, 2021)

- The State of Alaska has some of the highest rates of violent crime including domestic violence, sexual assault, child abuse and neglect.

- Alaska has some of the highest rates accidental death rates, obesity and sexually transmitted diseases in the nation.

- Alaska has some of the highest rates of suicide in the nation. Alaska’s suicide rate remains among the highest in the country — around 30 deaths per 100,000 people. It’s the leading cause of death among Alaska youth over the age of 15.

- Over the last few years, Alaska’s adolescent suicide rate has been about three times higher than the national average. Another alarming finding: the suicide rate among Alaska Native youth nearly doubled from 2018 to 2019. Suicide is currently the leading cause of death in Alaska for adolescents. The Alaska Careline crisis hotline saw a 51 percent increase in the number of callers this year, according to the state’s report

- Data from the 2019 Alaska Kids Count Report ranks Alaska 45th in the nation for children’s well-being based on 16 benchmarks related to quality of life, 50th in the nation for health, 49th in the nation for education, and 33rd in the nation for economic well-being.

PUBLIC WELFARE

- This term is perhaps the most ambiguous and far-reaching of the State’s Constitutional obligations. Technically, it is described as programs that provide cash assistance or services to individuals and families who are deemed eligible on the basis of their income and assets. It might be more helpful to think of it in terms of efforts to protect our most vulnerable, address inequities, and ensure the public safety.

- Vulnerability can be thought of as those Alaskans in need – this is measured by income levels, unaffordable costs, and conditions or circumstances that place an individual, family, senior, or child in an untenable position.

- Inequity is simply making sure that access to and relief from State investments of resources are felt across geographical or societal systems. It’s not that everyone gets the same thing, but that one group of Alaskans, or part of the state, isn’t disproportionately impacted over time.

- Finally, it is probably important to place public safety under welfare, as the two go hand in hand, and includes emergency response.

Public Welfare – State Public Assistance

- Medicaid – Provides medical assistance to needy individuals and families. Basically, it is intended to provide medical coverage for needy families with children, pregnant women, low-income adults, and aged, blind, and disabled persons.

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly Food Stamps) – Provides nutrition benefits to supplement the food budget of needy families so they can purchase healthy food and move towards self-sufficiency.

- Adult Public Assistance – Maximum $1,156/month for an individual and $1,719/month for a couple (as of January 2021.)

- Alaska Temporary Assistance Program – Maximum cash benefit of $821 for a family with 1 child, $923 for a family with 2 children.

- General Relief Assistance – Provides for emergent basic needs for shelter, utilities, food, clothing, or burial.

- Heating Assistance – Provides help paying for home heating costs.

- Senior Benefits Program – Monthly payment of $76, $175 or $250 depending on income.

- WIC (Women’s, Infants, and Children) Program – Provides nutrition education, referrals, breastfeeding support and benefits to purchase supplemental foods designed to address nutrient inadequacies and nutrition education.

- Child Care Assistance Program – Provides monthly subsidy to help with childcare expenses based on a sliding fee scale for eligible low-moderate income families.

- Chronic and Acute Medical Assistance – Provides emergency medical coverage for persons who do not qualify for Medicaid.

Public Welfare – PCE

- Power Cost Equalization (PCE) – The PCE program provides economic assistance to communities and residents of rural electric utilities where the cost of electricity can be three to five times higher than for customers in more urban areas of the state.

- The program is founded on the fact that the State made large investments into urban and railbelt infrastructure projects, which couldn’t be replicated in all Alaska communities. The funding available each year is formula-driven and provides an equitable baseline from which energy costs can be managed.

PERMANENT FUND

- While the data here is a few years old, the premise stands – sovereign wealth funds are common across the world. Many are tied to oil and gas development, basically transferring a non-renewable asset into a renewable asset, anticipating that the resource runs out at some point and the nation will need a sustainable source of revenue into the future.

- Alaska’s Permanent Fund is the only one in the world that pays a dividend to residents. This has the effect of diminishing the potential size that the Permanent Fund could be, even as it provides economic support for Alaskans.

- $26 billion in PFDs have been paid out since inception, which means that much less in Alaska’s long-term savings account. Coupled with the lost investment return from that amount, it’s a significant difference

Clearly, the PFD has increased over time, on all measures.

- The number of PFDs paid has increased, but also the gap between who is eligible and who is not, as a portion of the population.

- The total disbursed by the State has varied, reflecting market returns and the value of the Permanent Fund.

- The amount of the PFD has similarly varied, but it is easy to see why Alaskans could come to expect that about $1,000 seems like a minimum, or should be considered fair.

- Growth of the Fund, or the trend of the PFD, also means that there may now be expectations of growth in the distribution.

ISER’s literature research indicates that:

- The findings across papers show that the PFD has not had a negative influence on the labor market. In fact, there is evidence of small positive demand responses. Overall, however, the employment-related effects of the dividend are fairly small on annualized basis.

- More recent work using a detailed data set shows that Alaskans spend significantly more on non-durables1 and services in the month when they receive the dividend payment, and this excess consumption persists over the first quarter after the dividend payment.

- The evidence indicates that the PFD has a positive, but modest effect on birth weight. This effect is particularly pronounced for low income mothers. For three-year-olds, there is strong evidence that the PFD reduces obesity.

- The PFD has resulted in substantial poverty reductions for rural Alaska Natives. These effects have been particularly pronounced for the elderly.

- The PFD increases income inequality in both the short and long run.

- In the weeks following the PFD distribution, substance abuse related incidents increase while property crime related events decrease. Additionally, both substance abuse and medical assist instances are increasing in the payment size but there is no evidence that property crime is responsive to fluctuations in the amount.

PFD Reductions

- Alaska’s Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) is unique among the states, offering every full-time Alaska resident a chance to share in the state’s natural resource wealth. Annual payouts under the PFD typically range from $1,000 to $2,000 per person. But while every individual in Alaska receives the same size PFD, this payout is a much more significant source of income for families of modest means. While a $2,000 annual payment amounts to 2 percent, or less, of the income of an Alaskan earning a six-figure salary, its value is closer to 10 percent of income for a minimum wage worker bringing home roughly $20,000 in earnings per year.

- As a result, reductions in the PFD are steeply regressive, having a far larger impact on families with lower incomes. Figure 5 demonstrates that while a $784 cut to the PFD payout could free up approximately $500 million for Alaska’s budget, that gain would come at a high cost for Alaska’s most vulnerable residents. Low-income families could expect to see their incomes cut by 7.2 percent under this change while the impact on middle-income families would amount to 2.5 percent and high-income Alaskans would see impacts well below 1 percent of their incomes.

- The results show that the impact on the bottom 20 percent of earners (at 7.2 percent of income) is nearly ten times as large as the impact faced by the top 20 percent (at 0.8 percent of income).

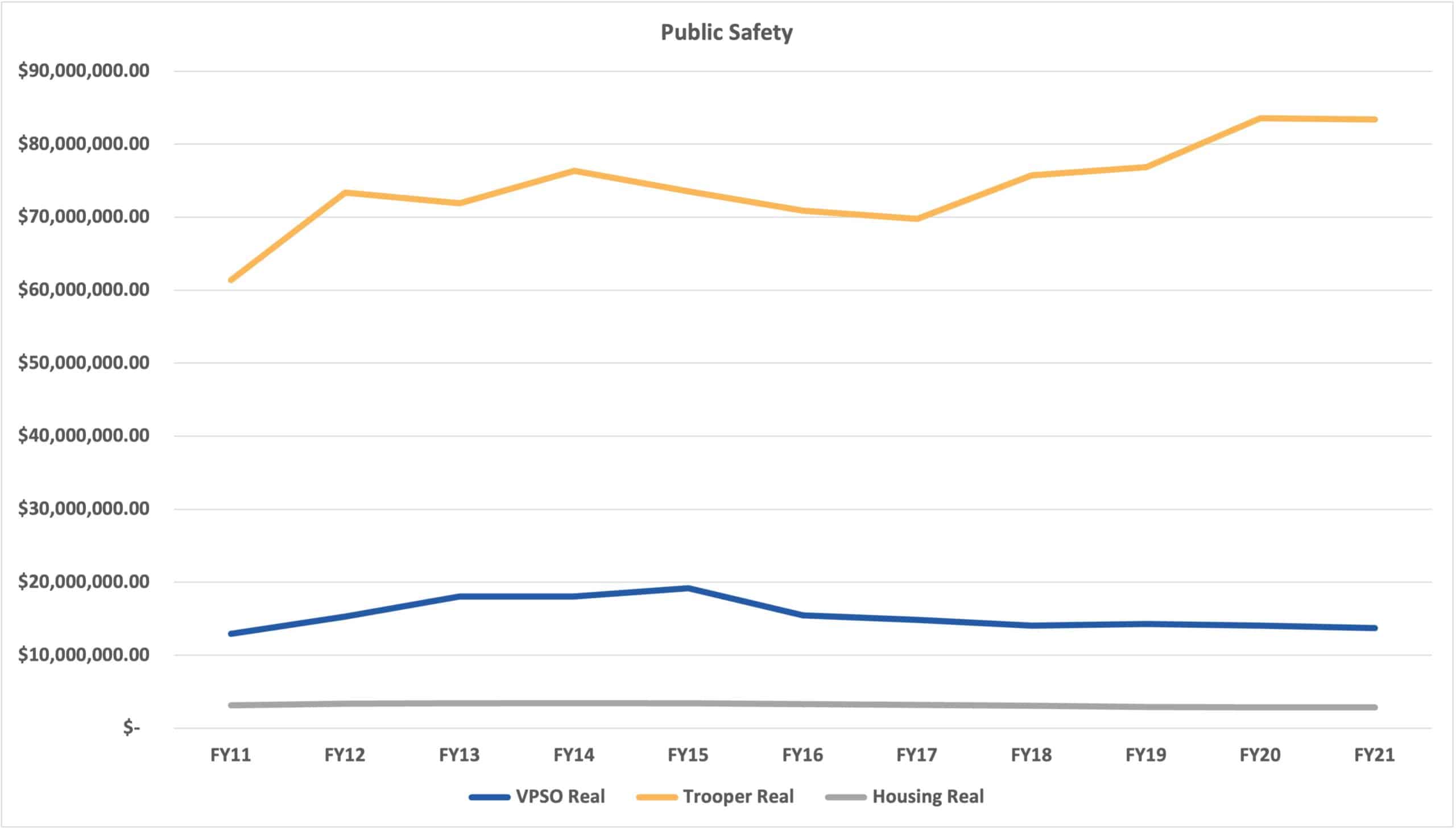

PUBLIC SAFETY

- There are 59 cities that have police departments or employ a municipal police officer – in rural communities these are referred to as Village Police Officers. This does not include VPSOs, which have a different role.

- A standard by which to evaluate public safety is the number of law enforcement per 1,000 residents. One metric that is common is 3.5 officers per 1,000 residents. Source

- By that measure, of those 59 cities, 30 of them need more officers per capita. That ranges from at least a half-time officer, to needing as many as 15. Anchorage, Juneau, and Fairbanks could be considered to need dozens more than that.

- If we’re looking at total number of officers in Alaska, including State Troopers, Alaska is more than 1,000 law enforcement officials deficient

Public Safety – Law Enforcement

- The VPSO launched program in 1979. In 2019, the number of VPSOs fell to an all-time low of 38 — compared with more than 100 in 2012. One in three communities, or 70 communities, have no police at all. The federal Department of Justice subsequently declared the public safety gap to be a federal emergency. As of February 2021:

- VPSO 54 Positions filled and 14 vacant

- 49 villages served (5 communities have 2 VPSO’s)

- 30 VPSO’s are certified

- 22 VPSO’s have under 1 year of service

- Many of these communities without law enforcement are in regions with some of the highest rates of poverty, sexual assault and suicide in the United States. ProPublica and the Daily News asked more than 560 traditional councils, tribal corporations and city governments representing 233 communities if they employ peace officers of any sort. Here is what was learned:

- Tribal and city leaders in several villages said they lack jail space and police stations. At least five villages reported housing shortages that prevent them from providing potential police hires with a place to live, a practical necessity in some regions for obtaining state-funded VPSOs. In other villages, burnout and low pay, with some village police earning as little as $10 an hour, lead to constant turnover among law enforcement.

- In villages that do have police, more than 20 have hired officers with criminal records that violate state standards for village police officers over the past two years. They say that’s better than no police at all. The review identified at least two registered sex offenders working this year as Alaska policemen.

- Alaska communities that have no cops and cannot be reached by road have nearly four times as many sex offenders per capita as the national average.

Public Safety – Troopers

Average State Trooper Position Counts:

- Over the last 10 years, the number of budgeted trooper positions peaked in fiscal years 2014 & 2015, with 425 budgeted positions. Moving into FY21, the department has 403 budgeted Trooper positions, which is an increase of 15 positions over the prior fiscal year. The department averages a 9.55% vacancy rate for the trooper job positions at the beginning of the fiscal year. The attrition rate for the trooper job class is determined based on the workforce size at the beginning of the calendar year. 2019 marked a 5-year low in the trooper attrition rates. 2015 was 7%, 2016 was 9%, 2017 was 7.7%, 2018 was 9.3%, 2019 was 6.9% (Data from Alaska Payroll system). Notably, approximately 44% of the department’s state trooper workforce will reach retirement eligibility in the next five years.

Public Safety – Corrections

- Estimated costs is $52,633 a person per year in prison. Corrections now costs the state more than the university budget. Since 2015, when adjusted for inflation, the Department of Corrections is one of the few agencies whose inflation-adjusted budgets has grown.

- 65% of inmates are mentally il

- 80% have some kind of substance abuse disorder

- 65% report some form of traumatic brain injury

- 5,100 Alaskans are in some form of facility with 4,300 in state prison. 13,000 Alaskans are either in prison or in some form of criminal justice supervision. Lost productivity due to incarceration in Alaska in 2018 amounted to an estimated $50.3 million, including $4.6 million from women (9%) and $45.7 million from men (91%) (McDowell Group).